Using the Dot Like Aboriginal Artists?

For decades now, there is an ongoing debate about whether non-Indigenous people should or should not use dots in ways similar to Aboriginal Western Desert painting, still among the most popular and recognisable of Aboriginal art worldwide. Some say that to sue it is to perpetuate the same arrogant, imperialist errors of the past. Others may say that art, quotation, and inspiration are pretty much open-slather in contemporary art.[1]

The best answer is that there is not a one-size-fits-all policy to these things: to appropriate (steal) imagery from a once (and still) oppressed people is very different people from when such people work in the style of the oppressor because in that case, they usually have little choice than to do so.

I see every spot within each painting as being alone yet together with all the other spots.—Damien Hirst [2]

Start with a Personal Anecdote

I have a friend, Indigenous, who has a tattoo on his left shoulder. It is the map of Australia styled from boomerang shapes and the Aboriginal flag. The same friend sent me an email with a photograph of a Canadian man with a tattoo of a maple leaf bearing the motto, ‘Made in Canada’. The message was sent with contempt at the man's nationalism. But why had he the right to do so if he, too, wore a similar branding? Was this hypocrisy?

No, the difference between the unfortunate Canadian man and his tattoo was that one was worn out of pigheadedness, and the other was a sign of resilience and defiance. <<One instated tautological ownership (I am what I already am), while the other laid claim to something he didn’t have.>>

One mistook claim for essence – the recent creation of a state, in this case, Canada – while the other asserted the essential character of his claim. One was about possession, the other about loss.

The Question of the Dot

Suppose we apply this same logic to the question of dots in Aboriginal art. In that case, we might say that the emotional possessiveness of most Aboriginals to the dot is not simply because it is a social identifier, but, like 'country', it is because of their nominal ownership of it, since the invention of Aboriginal art in 1971, has always been imperfect and incomplete.

<<Their stakes in ownership are arrived at through dispossession. Non-indigenous people 'inhabit' the world of images, in which ownership is arbitrary and taken for granted. For the Aboriginal, the dot is talismanic, for the non-Aboriginal, it is anecdotal.>>

This schism between talisman and anecdote is hardly new or exclusive to Aboriginal peoples. The best example of the difference between ritual ownership on one hand and sampling (or appropriation) comes with tattooing because it is the act of violent inscription upon the body.

It is not only painful and permanent but is either additive or constitutive of identity. Additive applies when the tattoo is obtained by choice, constitutive when it is a marker of initiation. In the latter case, the word 'obtained' is too vapid since the application of the tattoo is itself the conclusion of the ritual passage that both distinguishes a member of the group and ensures his membership to it.

The Example of the Tattoo

The tattoo is also the best exemplar for understanding the difference between sacred and ritually oriented– or as far as what anthropologists call ‘ritually integrated’ – societies and secular, rationalized ones. This difference is best seen in Japanese Samurai and Maori tattoos. These were traditionally done by hand, which meant the application was more painful, but to endure this pain was a pivotal component to the warrior's mettle. Be it combat or formal recognition, the warrior wears his tattoo as an aesthetic celebratory wound.

Now it is possible to buy, for a relatively small price, what for the warrior came at considerable personal effort and risk. We can buy the trophy of a rite of passage without having to undergo its rigours.

One can choose one's fealty to a tribe, totem, or myth. The world is yours, just not its inner substance.

That tattoos are worn on the body permanently exposes the difference between the two approaches yet more – one is an outward sign of an inner, spiritual and pathological state, in which there is a homology between self and idea, the other is an outward sign of a personal aspiration that draws vampirically from the first condition.

In short, the wearer of the modern tattoo buys into a system and a culture but whose belonging is entirely self-indulgent and presumptuous.

White People Who Play Loose With Dots

This detailed analogy is apposite to the debate surrounding the appropriation, or misappropriation, of dots and other recognizably Aboriginal artistic styles that have hit a high pitch in the last year or so.

It was noticeably sparked by Lucas Grogan and succeeded by the controversy amid some Aboriginal communities over Del Kathryn Barton's Archibald Prize-winning portrait of Hugo Weaving.

The former case has already been canvassed earlier in these pages, while the latter has already enjoyed a drubbing over social media, particularly on Richard Bell’s Facebook page. Barton’s portrait is in her now familiar laboured style, and the work put to rest any doubts that the Archibald Prize’s love affair with caricature has dwindled.

The work depicts an uncomfortable, stolid, and mildly constipated looking Weaving interlocked with an exotic looking cat whose startled look can be attributed to the fact that its tail resembles a snake. Weaving has a garland of eucalypt leaves around him that, equally improbably, have turned the colours of deciduous trees.

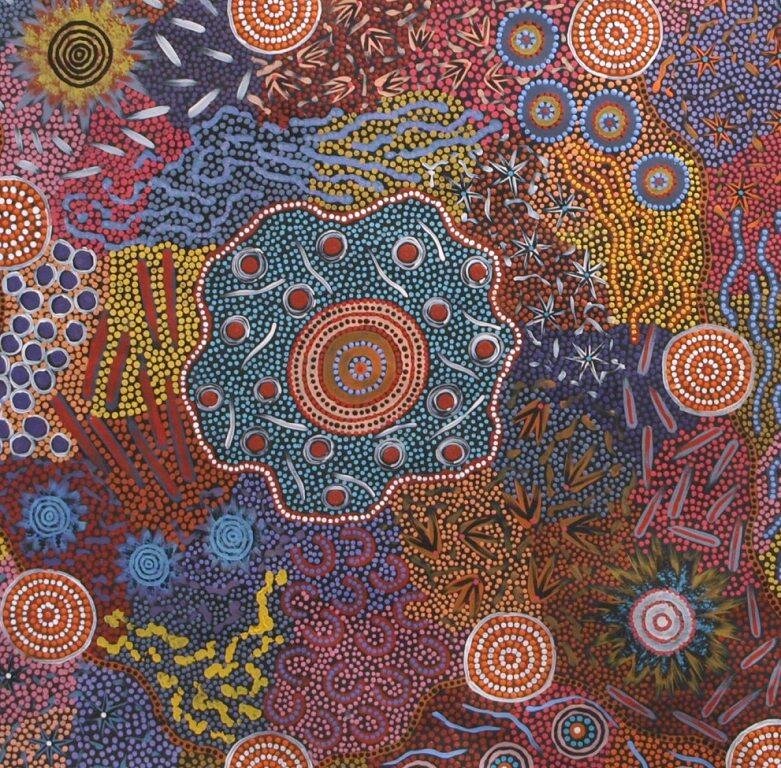

He sits against a sort of firmament of dotted diamonds or leaves, redolent of the classic Tjakamara Papunya Tula painting, except the colours are mostly green and turquoise. The resemblance, however, is unmistakable. Barton has domesticated and ‘eucaliptified’ the sacred designs of the hot and remote region of the Western Desert by rendering them in cooler colours.

Now Let’s Scratch a Bit Deeper

But let us scratch a little deeper. Barton has lent her hand to the likeness of an actor who is not only non-Indigenous but who was born in England. Some may call him an Australian actor, and yet Wikipedia has him as an English actor.

It is darkly ironic that a recognizably Aboriginal style of painting specific to the dreaming of a particular region has been adapted for the sake of promoting an actor coming from the very empire that colonized these people and subjugated them for over two hundred and twenty years.

This is in no way to discredit Weaving himself – far from it; it has nothing to do with him, his character, or his talents as an actor. But we must try to examine this issue in a broader and more objective light.

After the win, Australian Vogue ran a short promotional story that describes how the artist wanted to depict 'a sincere, deep, generous and creative soul'.[3] <<I’m unsure whether she succeeded, although she did manage to convey the registers of a gastric or some other uncomfortable disturbance such as holding a bad case of flatulence.>>

What is more disturbing is the word ‘generous’. Again, external to a derogatory reference to Weaving himself, what we have is the very obverse of generosity, in stealing from a people who continue to live in squalid and makeshift conditions, well below that of most non-Indigenous people to win a prize worth a hundred thousand dollars.

It is easy to assert that the dot pattern around Barton's subject lent her painting an aura of spiritual grace, depth, and authenticity. Much as a biker gang member may get a Samurai tattoo emblazoned across his back to show that he shares the same instincts as Japan's venerable warrior priesthood, Barton availed herself of the Aboriginal dot designs to ensure her work exuded the fair share of legitimacy.

But from here could be mounted the objection that the dots in this picture were ‘just dots’ much as Freud famously stated that ‘sometimes a cigar is just a cigar’. Of course, there is no precise delineation.

When’s a Dot not a Dot?

It would be absurd, for example, to accuse an artist known for the use of dots, such as Yayoi Kusama, on these grounds were she to exhibit again in Australia. However, how Barton arranges the dots makes the analogy all but unmistakable. To mount an argument that it was unintentional still courts similar objections.

For inadvertently to do a swastika design at an Israeli art festival is to be guilty of not seeing it as such and altering it accordingly. But in the case of Grogan, to appropriate as he did Aboriginal art to such an overt extent is doubly outrageous.

It may have had some weight if he had done so in dialogue with Indigenous artists and had done so in the name of ‘the cause’, say in a work that deals with Aboriginal identity's continuing stereotypes.

But the opposite is the case, Grogan was adding to this very problem of exploitation and flagrant neglect: he was doing what he did because he could, and for his own personal profit. Writing recently in Artlink, Maurice O’Riordan, comments that

Grogan himself was reputed to have had some 'breakdown'. This is unfortunate, if true, but so, indeed more so, is the flagrant disregard for Aboriginal copyright, particularly when enacted consciously, as with Grogan's case. With an apparent hunger (at least initially) for any publicity, his 'transgressions' could garner.[4]

So while it would be naïve not to know that all are available in our image-ready times, to have presumption over delicate content comes with consequences.

<<Grogan is undoubtedly not sensitive to the fact that art was the single most significant driving factor in giving Aboriginal a firm place within white Australian culture:>> it not only gave them self-esteem that they were doing something of value, but it gave them visibility in places where they in the past (or even now) would not have been permitted entry, least of all into the residences of the wealthy and powerful.

While the incongruencies of this are deeply moot, it is for this compromised situation that has made Aboriginal art the single biggest artistic export, with regular auctions dedicated only to it occurring abroad, notably in New York.

The Importance of Aboriginal Art

Non-Indigenous artists have accomplished no such feat, and it is unlikely in the near future either. Robert Hughes proclaimed Aboriginal art the last great art movement of the twentieth century. Even if movements had ceased to have the same validity at the end of the twentieth century, and even if Aboriginal art is Aboriginal art and not a movement, however obtuse or sententious this statement can be taken to be, it is still worth citing for the reason that it could never plausibly apply to the art of white Australia.

The dot can be understood as the stylistic sine qua non of this achievement. It is central to the Aboriginal ‘brand’, which is significant to Aboriginal livelihood and the mainstay and evolution of its identity.

Before Aboriginal art co-called invention in Papanya in 1971, the original dots are pertinent to this region were much larger and originally not executed on board or canvas. Rather, they were much larger indexical signs executed in the sand as part of the process of sharing stories or of invoking totemic animals in ritual.

The resultant forms or designs were only there as a component to the telling – which could also involve song and dance – and was removed once the ritual, or storytelling event, was ended.

The design itself was also not art per se. Like many cultures (including the ancient Greeks), especially those with a rich ritual awareness, Aboriginal cultures had no word for art and no place for it. The practices that the Western concept associates with art were part of a much larger complex of sacred activity.

By extreme contrast, what became art was now permanent instead of ephemeral marks in the sand.

This radical alteration in spiritual representation immediately caused several objections within certain Aboriginal communities themselves. The earliest debates amongst elders were the exposure of sacred designs to non-initiated eyes, whether they were clan or complete outsiders.

How Do Dots Function in Aboriginal Art?

The dots, it is often observed, as they evolved in the ensuing decade, became finer, more gauze-like to act as a covering layer for the secret and sacred content beneath. In acting a protective skin, the dot assumed greater significance, as something for itself and an intermediary between iconography not to be disclosed and the outside world.

Since then, the dot has come to have talismanic significance for Aboriginal art and artists well beyond the boundaries of the Papunya region.

In the words of Indigenous artist and film-maker Janelle Evans,Suffice to say, though, that when white Australians discover they have Aboriginal heritage, one of the first things they do is try to ‘learn’ how to be Aboriginal - this includes painting ‘Aboriginal Art’ using dots – ‘Ooga Booga Art’ (coined by ProppaNow).[5]

It is fair to argue that the dot in the Papanya sense assumed far more universal importance once Aboriginal art was ‘invented’ or conceived.

With the displacement from sand to canvas or board, specific motifs and styles became hypertrophied and appropriated by other Indigenous people. Its closest ally in this renegotiation of objects and styles, once specific to language and region, is the didgeridoo.

Most people in Australia – and one could also assert some of Indigenous heritage – believe it to be the national instrument of Indigenous people, which it has become, although it belongs to a relatively small region of the north-east cape of Arnhem land belonging to the Yolngu people. Its proper name is the yidaki, didgeridoo being the onomatopoeic pidgin.

The Western ‘Invention’ of Aboriginal Art

But on the other hand, one cannot help feeling sympathy with the mockery that the collective ProppaNow level at such a practice, because it is very the symptom not just of the Western-oriented 'invention' of Aboriginal art, but also its marketing and proliferation.

Dot paintings are among the most popular because they are not only associated with Aboriginal art's 'birth', but because they appear decorative. Add to that, they show the visible signs of manual labour, which is always a winning component to lay purchasers of art (with Barton being another beneficiary of this banal truth).

Michael Nelson Tjakamara

The work of Tjakamara and other greats like Johnny Warangkula Tjupurrula is that their stunning diaphanousness has a profoundly seductive, hypnotic quality. But the undeniable aesthetic qualities of such work have also led to an ongoing concern about Aboriginal art and its sacred content that not only do most buyers have no knowledge of this content, nor have any right to it, their response to it is according to the work’s sensuous, decorative qualities, qualities that are given a turbo boost of legitimacy for the gravitas of the promise of unspoiled, innocent spiritual profundity.[6]

The fact that the Papanya dot has now adorned a famous BMW, airplanes, and the Qantas uniform makes it all close to a ubiquitous sign of Aboriginality. But usually, as with Michael Nelson’s famous M3 BMW or the Qantas uniform, the design exists as a safe remnant, with the people and their place remote from the motifs and practices that were once seamless with it.

These issues do not, however, dampen the importance of the founding Papunya painters, but it does, however, add complexity to the use of dot painting by young artists today.

Aboriginal Urban Artists

There is also a generation of eminent urban artists who have successfully used dots in their work, such as Gordon Bennett, Lin Onus, and Harry Wedge. Their work has helped shape and characterize how urban Aboriginal art is understood today, using individual styles and motifs in a meta-textual manner.

In other words, an image or style can have more than one meaning, which may bear reference to how Aboriginal culture is exploited or misconstrued. In this vein, the dots (or additionally in the case of Onus the rarrk) come to assume an ironic but conceivably also a tragic import; the use of a style not belonging to the people with whom the artist identify is a strategy to reach to more than one Aboriginal people, given that subjugation is something that they all share.

Such artists are not profiteering from their appropriation of these motifs and styles as they typically have much at sake, for the sake of themselves and the collective.

Appropriating Aboriginal Art

There are non-Indigenous artists, Imants Tillers and Tim Johnson, for example, who have appropriated Aboriginal art. They have done so in collaboration or with permission from certain Indigenous groups. Permissions are not universal, and some Aboriginal people feel conflicted about what they see as opportunism.

It is the issue of what is at stake is at the core of the debate. When a non-Indigenous artist like Grogan appropriates a style so flagrantly, he is not speaking in the name of a people, nor does he have the burden of oppression behind him. For any Aboriginal artist of quality, traditional – although these designators have changed in the last couple of decades – and urban, the style, method, and content of the image comes various degrees of responsibility and questioning.

Given the disgraceful and embarrassing fact that our Indigenous peoples, as I write, are not in our national constitution, all Aboriginal art, whether or not it is sacred – is also political. This leads me to the content at the beginning of this essay. The tattoo of the flag in second place of a people yet to receive the respect they deserve is a solidarity and struggle statement. In contrast, a tattoo of a flag, especially one from a post-colonial country, is ignorant neocon kitsch.

Maybe one day, in an Australia which has finally lost its tokenism and its lip service, that has changed its national day to something that is not a reminder of occupancy, violence, and enforced law, when education and recognition of the 'true' past are no longer uneven but normative and widespread, then things like dot patterns might be more freely circulated between white and black. But not yet.

Post Script

I began this essay with no ulterior intention while preparing the exhibition BOMB with Blak Douglas (aka Adam Hill) at the Aboriginal Art Museum in Utrecht (AAMU), Holland. The show's centerpiece is a 1989 3-series BMW, of the same generation also the Michael Nelson car. We executed what we have called the 'Dorian Gray's face' of the historic vehicle, not as a criticism to the artist but rather to the decontextualisation of Aboriginal art in general. The BMW is of a piece with the air-conditional white wall display halls for art produced in sun and dust conditions. It is a vehicle that most Indigenous would buy, let alone afford, and it uses a fuel that plays a role in despoiling their land. Our BMW, the 'Bomb' was painted with a huge union jack in dots. Where this places me, I am unsure, but the message was pretty straightforward.

References:

[1] I am grateful to my friends and colleagues Blak Douglas (Adam Hill) and Janelle Evans for their lending insights while writing this essay.

[2] Damien Hirst, cit. Gordon Burn, ‘Is Mr Death In?’, Damien Hirst, I want to spend the rest of my life everywhere, with everyone, one to one, always forever now, New York: Monacelli Press, 1997, 9

[3] Vogue Australia, 22 March 2013, http://www.vogue.com.au/culture/arts/del+kathryn+barton+wins+archibald+prize,22835

[4] Maurice O’Riordan, ‘The (White) Elephant in the Room: Criticising Aboriginal Art’, Artlink, *****

[5] Email correspondence, 30 June, 2013.

[6] See also Adam Geczy and Adam Hill, ‘Aboriginal Art Diagnostic’, Contemporary Art + Culture Broadsheet, v. 40, no 2, 2011